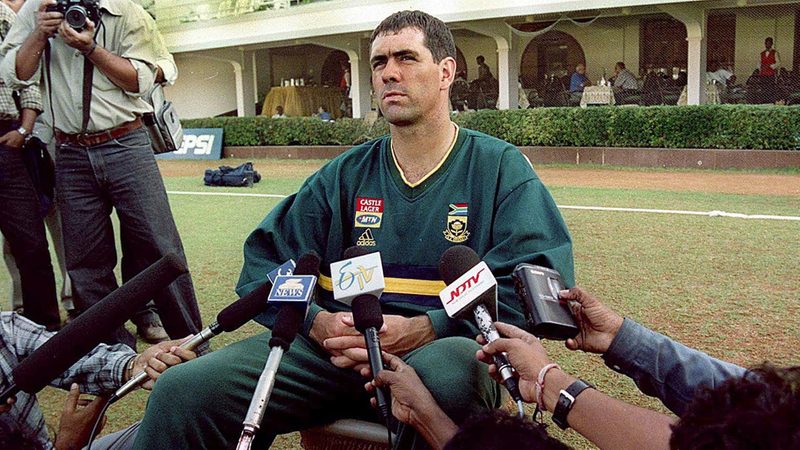

It may be two decades since the Hansie Cronje corruption scandal rocked cricket, but even now the ripples are still being felt.

This month marks the 20th anniversary of Cronje being stripped of the South Africa captaincy following an extraordinary sequence of events earlier in 2000.

In January, come the last day of a 'dead' Test against England (South Africa had already won the series) a draw seemed inevitable after rain had washed out three days' play.

Yet Cronje contrived a positive result by getting England captain Nasser Hussain to agree that both sides would forfeit an innings.

England were left with a target of 249 for victory after Cronje declared and eventually won by two wickets.

Traditionalists were aghast at the interference with the 'proper' course of a Test, yet few were prepared for what was to come.

In April, Cronje's image as a religious sportsman -- he wore a bracelet inscribed with the words 'What Would Jesus Do?' -- was shattered for all time.

An AFP report, later confirmed by the New Delhi police, said the force had phone recordings of Cronje and an Indian bookmaker discussing predetermined Proteas' performances during their tour of India the previous month.

Such was Cronje's standing at home and abroad, the initial reaction was one of "shock and disbelief" according to one of South Africa's leading cricket writers.

It was a sentiment shared by Dr Ali Bacher, the managing director of the United Cricket Board, the forerunner of today's Cricket South Africa.

- 'Look for another job' -

"When AFP broke the story before the official press conference by the Delhi police, I remember the office receiving a call from Dr Bacher blasting the agency for ruining the reputation of one of South Africa's most iconic personalities," recalled Kuldip Lal, the Delhi-based cricket reporter behind the scoop.

"He threatened to sue us. I thought to myself that if the story is incorrect, a few of us may need to look for another job."

But Cronje's partial confession a few days later led to a "feeling of relief" in AFP's Delhi bureau, with Lal adding: "To his credit, Dr Bacher called the office to apologise for his earlier outburst."

Cronje later confessed to several allegations at the South African government-appointed King Commission, including attempts to bribe Herschelle Gibbs and Henry Williams to underperform in a one-day international against India.

He also admitted to receiving hundreds of thousands of dollars from bookmakers to prearrange certain conditions -- cricket's complexity means gambling coups are possible without 'fixing' the result -- with his Centurion effort netting him some $6,000 and a leather jacket.

Cronje, who insisted he had never thrown a game, was later given a life ban from cricket yet his reputation remained high with both his former team-mates and the South African public alike.

For example, batsman Daryll Cullinan, testified Cronje, who died in a 2002 plane crash, had offered the team $250,000 to throw a match before adding he still thought of him "as a great captain and a great leader".

Meanwhile separate national hearings and investigations led to life bans for Pakistan's Saleem Malik and India's Mohammad Azharuddin.

Yet their suspensions were among several punishments subsequently overturned, although for Malik and Azharuddin the initial sanctions effectively ended the careers of two world-class batsmen.

The International Cricket Council responded by creating a new anti-corruption unit led by Paul Condon, the former head of London's Metropolitan Police.

But it was desperately under-staffed and 10 years ago it was Britain's now defunct News of the World tabloid that exposed the willingness of Pakistan captain Salman Butt and bowlers Mohammad Asif and Mohammad Amir to engage in spot-fixing.

Since then a beefed-up ACU, respected for its work in educating players about the dangers of corruption, has had a greater impact, with its investigations leading to New Zealand batsman Lou Vincent receiving a life ban for match-fixing in 2014.

But the rise of Twenty20 franchise leagues and the development of the sport beyond top level men's cricket have created new targets for fixers.

As has happened in tennis, they can now turn their attention to less high-profile areas of the game, where the financial rewards for players are far less and the temptation to cheat potentially all the greater.

One constant though is that betting on cricket in India, the sport's biggest market, is illegal, meaning there is no formal regulation, even though gambling on horseracing is not.

Feature image courtesy: AFP / Sebastian D'souza